The River Shall Live: An Introduction to Healing the Damned

Zambia’s wide network of rivers has long been central to the livelihoods of communities who depend on their natural flow for sustenance and spiritual continuity. Among these waterways, the Zambezi River has held a particular sacredness. It is more than a source of water or food; it is a living archive of memory, ancestry, and cosmology. Yet this deep relationship between people and river has been disrupted by the imposition of colonial and postcolonial development projects, whose hydroelectric infrastructures have scarred both land and life.

The construction of the Kariba Hydroelectric Dam between 1955 and 1959 marked one of the most violent ruptures in this continuum. Built under the colonial Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, the project sought to generate electricity for the mining industries of Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), as well as for the white urban settlements that benefited from them. Behind the rhetoric of progress and modernisation lay an entrenched logic of extraction that prioritised economic ambition over human and ecological balance.

The Kariba Dam became a trophy of imperial engineering, commissioned by the British, designed by French architect André Coyne, constructed by the Italian company Impressit, and financed by an US$80 million loan from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (now the World Bank). For colonial powers, it represented mastery over nature and the ability to bend the river to human will. For the 57-110,000 baTonga people who lived along the Zambezi in the Gwembe Valley, it meant dislocation, dispossession, and the loss of ancestral lands, shrines, and cultural continuity.

baTonga were displaced from fertile riverbanks to the dry, unyielding plateaus of Lusitu, Chirundu and Sinazongwe. They became, in effect, environmental refugees within their own homeland. The dam altered fish populations, reduced water quality, and disrupted the ecological systems that had sustained generations. Yet even as the colonial narrative of development drowned their world, baTonga resisted.

Between 1955 and 1959, the Gwembe Valley became the site of sustained, though often silenced, protest. Resistance emerged through petitions, appeals, community gatherings, and acts of spiritual defiance. When the dam’s construction was announced, Harry Mwanga Nkumbula, leader of the Zambian African National Congress (ZANC), petitioned the Queen of England to halt the project. His plea was dismissed as illegitimate, and the colonial government pressed forward, determined to complete what it saw as a monumental achievement of empire.

On the ground, baTonga mobilized through ancestral and political channels. The most forceful resistance unfolded in Chisamu, a village in Chief Chipepo’s area, where community leader Siaganka played a key role in encouraging defiance against forced relocation. After being arrested and imprisoned for “illegal congress activity,” he returned to Chisamu to continue organizing. The community refused to move even after floods in 1957 submerged their homes. They returned when the waters receded, signaling their refusal to surrender ancestral ground.

The colonial administration responded with increasing repression. In May 1958, Article 43 was ratified, making it a punishable offense to resist resettlement. Later that month, when a District Officer attempted to negotiate with the headman of Sianzimbwe and was rebuffed, a protest ensued. British colonial forces reacted by sending armed platoons to enforce removal across the valley.

Chisamu remained the stronghold of defiance. When the troops arrived, baTonga sounded the Budima drums, the drums of war, for the first time since 1898. They gathered in their hundreds, singing, dancing, and advancing toward the encampments with spears and chants of “We are Nkumbula’s men, and this is how we fight.” The confrontation lasted four days. On 10 September 1958, after teargas failed to disperse the protestors, the colonial forces opened fire. Eight were killed and thirty-two wounded.

The Chisamu Uprising, though brutally suppressed, remains one of the most significant moments of resistance against colonial infrastructure in Southern Africa. It represents not merely opposition to displacement, but an assertion of spiritual and ecological sovereignty. For baTonga, the struggle was not just for land but for the continuity of relationship between people, ancestors, and the river itself.

After the completion of the dam, the praxis of colonialism took on a new life. With the river now contained and conquered, the white man had finally subdued an insofar unconquerable territory. The dam became both a technological and symbolic victory, a reordering of nature that gave rise to a new mode of colonial presence. This facilitated a shift in language, style, and control. White settlers, who had once considered the region inhospitable, began to establish what historian Dane Kennedy has called “Islands of White.” These were isolated enclaves far removed from the people and ecologies around them. In these settlements, the colonial identity reinvented itself as one of care — care for the environment, for wildlife, for the preservation of a landscape they had violently transformed. The people who had lived symbiotically with that landscape for centuries were now cast as threats to it, as poachers and intruders. Colonial control adapted to this new order, translating its domination into the moral language of protection and conservation.

By 1959, most of the remaining communities were forcibly relocated. The resettlement areas were unfamiliar and infertile, leading to the loss of traditional livelihoods and the erosion of cultural practices tied to the river. The dam, while celebrated internationally, stood as a monument to both technological achievement and colonial violence, a structure that literally and symbolically divided people from their source of life.

In the present day, the legacies of Kariba continue to reverberate. Zambia faces recurrent power shortages, exacerbated by drought and declining water levels in the Kariba reservoir. The environmental and social consequences of hydroelectric dependency have become increasingly visible. Meanwhile, the proposed Batoka Gorge Hydroelectric Project threatens to replicate these cycles of displacement and ecological disruption. The past, unresolved, returns in new forms.

Healing the Damned arises from within this history, not to retell it, but to listen to what has been submerged. It seeks to trace the fractures between progress and dispossession, and to honour the memory of those who resisted and continue to resist by holding the river as a living witness. Through revisiting these suppressed narratives, the work opens a space for reckoning with the colonial infrastructures that continue to shape Zambia’s waters, lands, and futures.

Public Showings

2025

Healing The Damned Participatory Film Workshop, Reassemblages Symposium, G.A.S, Lagos, Nigeria

Healing the Damned: Group Exhibition, Forest for Trees Collective, New York, U.S

2024

Healing the Damned: Group Exhibition, Lofoten International Art Festival, Lofoten, Norway

No Conquest of Time, Nature and the Cosmos

Short Film (Stills)

6m24

2025 (Rework)

“No conquest of Time, Nature and the Cosmos” is a three-part audio-visual poem that rejects the violent fantasy of mastery over the world. Structured as movements on Time (Ciindi), Nature (Meenda, Lupani, Musila), and the Cosmos (Mulalabungu), it weaves English and CiTonga verses to remember ancestral ways of knowing that resist containment and conquest. The poem meditates on colonially imposed ruptures. Tar, dams, plastic and their scarring of time’s shadows, river channels, and the land’s red hills. It calls instead for a symbiotic relationship with water, wind, soil, and stars, listening to mourning drums and ancestral fires, tracing ochre-stained paths of kinship. Accompanying the poem is a spliced edit of Captive River, a colonial-era film, which serves as a visual critique, dissecting the narratives of domination embedded in the archive. By rupturing and recontextualizing this footage, the work exposes the entanglement between imperial image-making and the destruction of land, life, and cosmology. Ultimately, No conquest of Time, Nature and the Cosmos positions the cosmos as guide and witness: a constellation-compass for those seeking balance beyond the destruction of conquest.

naMusampizya

Speculative Fiction

2024

Musampizya (2024) the first project under this umbrella recodes Artificial Intelligence as Ancestral Intelligence using the frameworks of Radical Zambezian Reimaginings. This methodology which accepts and prioritises fictive realities as being a necessary component in the healing of critical gaps in history, especially those of marginalised and silenced people and communities. The series of images which have been generated in the absence of images (free of colonial violence) imagine and place baTonga at the site of the dam, and in the surrounding forests and plains before it was built.

The series of rendered self-portraits, uses digital technology to challenge the way in which the history of places like Zambia, have been told by Western Historians and Researchers using conventional colonial mediums such as text and analogue photography. The short film uses the technology to time travel, showing fictive histories and fictive futures from 1955 to 2055.

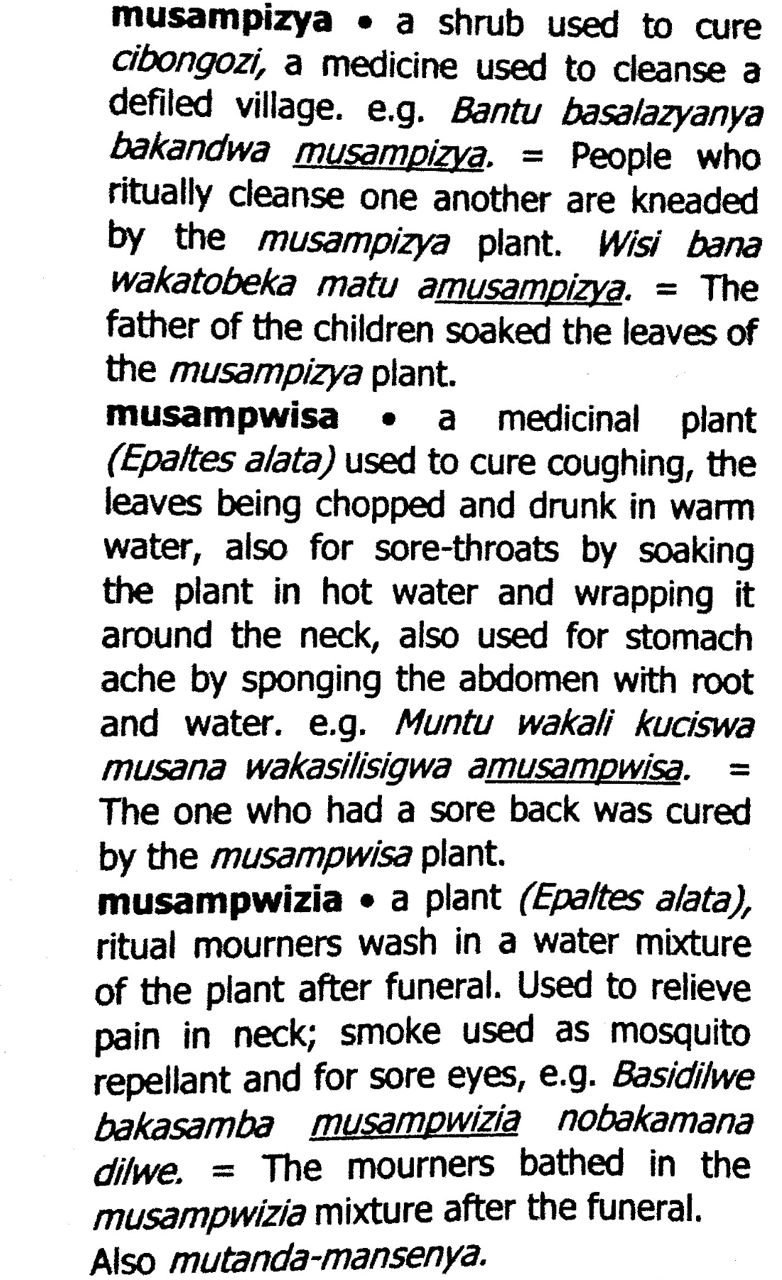

The name of this piece is borrowed from a shrub

that grows in areas in which baTonga lived and

live. It is a plant that served in various functions in

the world view of baTonga as both a cleansing

herb and a medicinal herb. I Imagine the spirit of

this (digitally alchemised) ancestor,

Namusampizya still roaming around the Gwembe

Valley looking for (and finding) all the sweet

smelling shrubs like epaltes alata to cleanse the

soil and homes of her Mukowa (future kin.) The

background is layered with a digitized image of

musila (red ochre) on canvas, a piece that’s been

hanging on my walls since I begun experimenting

with making natural paints.

Character stories

Character Stories is driven by the visceral need to attribute and reconstitute the instrinsic, non-exploitable value of baTonga women. It also exists as a direct challenge to the normative visual conceptions and projections of baTonga women found in the mainstream archive. baTonga women, in contemporary and historic visual culture, are often presesented as products, subjects or objects which exist as part of largely asymmetrical visual corpus mostly cemented by the western schools of Anthropology/Ethnography. Schools of thought whose foundational theories (and legitimacy in many ways) relied on the camera’s ability to capture curated scenes which corroborated the pre-conceived and often violent hypotheses of their carriers.

A number of photographs or videos of baTonga women which exist in the archive, mostly in public museums or private galleries in the occident, are often subtitled with the text “photograph of an unknown woman” and are devoid of any further data which alludes to the very core or centre of the photograph. This approach, renders baTonga women appedages of oppressive histories and narratives as opposed to autonomous agents of free will.

Character Stories challenges this gap in the documentation of dignified existences of baTonga people by virtue being written as people with recognizable and traceable names, extensive stories, timelines, families, hobbies etc.

Namusampizya is the name which has been given to the digitally alchemised ancestor shown in the series of images. She was named by her great-grandmother Luba who was a Sikatongo (earth priestess) and thus an oracle of sorts. Tonga naming traditions children either inherit ancestral names or are given names which reflect the charcter of the child or will reflect their charcater later on in life. Namusampizya translates as “mother of musampizya” a reference to her future fixation with sweet smelling shrubs such as epaltes alata and her work as an indigenous “botanist”.

She was born in approximately 1904 in a small village which was erased from the maps and the memory of people in the Gwembe Valley after the 1958 flooding of Kariba. In her teen years, she saw an apparition of her grandmother which asked her to spend twelve uninterrupted hours meditating underneath a Musikili tree. She listened. After feeling a connection like never before, Namusampizya dedicated her life to translating the language of plants into ciTonga through making oils and perfumes which she traded throughout the Gwembe Valley and into the Plateau in areas like Nampeyo and Haanjalika.