cisita is an on-going project based on the exploration of baTonga corporeal expressions. The project follows the methodology of Radical Zambezian Reimaginings, a portal that leads to the creation of alternative perspectives that challenge and repair pre-existing asymmetries in history, wounds that have informed the present. Rooted in the belief that ancestral buTonga personhood and methodologies hold immense intrinsic value which are yet to be recognised and given space within postcolonial imaginations. This approach challenges the hegemonic notion that baTonga are merely subjects and appendages of Western histories, imaginations and enquiries.

Existing research and archives on baTonga are mostly rooted in asymmetrical projections and narratives that have been conceived and published within and through oppressive frameworks and institutions. I counter this through actively positioning myself as a muTonga in the field of research and archival practice as being central to constructing a counter-narrative which seeks to heal historic and present day wounds through community. Through research and artistic production, cisita aims to explore, rework and critique contemporary narratives around baTonga corporeal expressions as well as centre the reclamation of the connection to nature and the botanical world as a way to heal and critique the asymmetries and violent projection encased within many expressions of the post-colonial imagination.

Corporeal expressions, body modifications and adornments were part of spheres of expression central to buTonga personhood. Like many other baTonga markers of identity, they were heavily impacted and to many degrees phased out during periods of external socio-cultural intervention. During colonial rule, baTonga adornment and body modification practices, such as kubangwa, the knocking out of the six front incisors and canines, of mainly girls and women, were forbidden by law and were fineable through systemised subjugation of the practices by ‘native authority law’. This further cemented the process of the diminishing of the practice(s). Inversely, little to no documentation exists, without violence and bias, in mainstream the archive and in collective memory.

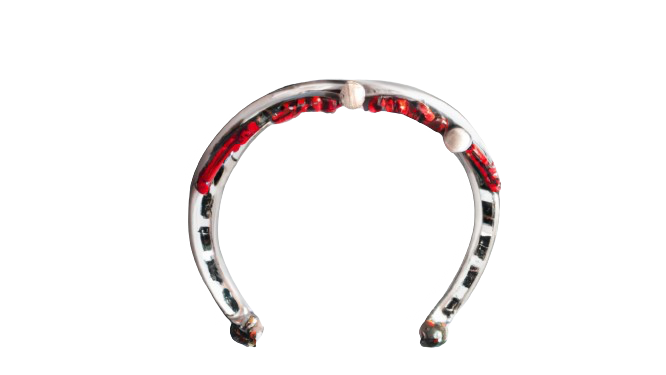

The research, in part, is centred around exploring and unearthing the archive of various natural or botanical processes of baTonga knowledge, technique and ritual that surround cisita, a septum piercing often donned by baTonga women.

PART I

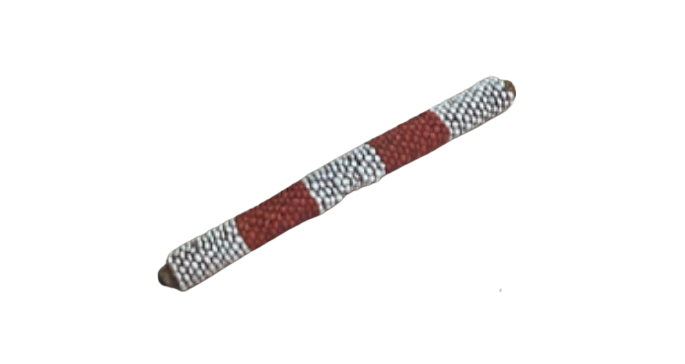

Living history tells of grandmothers piercing the septums of young girls and women with the thorn of mukoka (acacia tortillis) and thereafter sterilising the wound with an oil alchemised from the castor plant (Ricinus communis). cisita was then plugged and dressed with natural materials, first a young, thin stalk of matete, river reed as the piercing healed. Thereafter sorghum stalks, porcupine quills and delicately beaded casings for thicker stalks of reed would be worn in cisita. cisita was worn on various communal occasions but more so, as the woman as the wearer would see fit. An element of freedom and outward expression of a muTonga woman.

The focus of this element of enquiry is the centering and radical repositioning of the freedom of expression of baTonga women as expressed through their symbiotic relationship to the natural world and botany as reflected in the various processes and techniques of cisita as an object and a process.

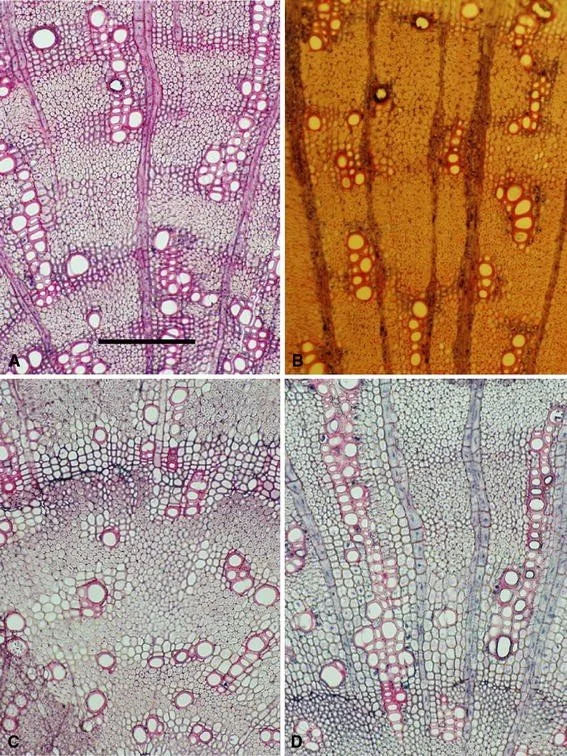

Artistic production will be presented through various physical outputs such as plant micrographs and sketches, poetry and audiovisual installations.

mukoka (acacia tortillis), plant micrograph

mabono, castor plant

alexander ruiz/Getty Images

woman photographed in Makongo Village, located on the Southern edge of Lake Kariba in the Gwembe Valley (2015) with her cisita plugged with matete

Stills from a BBC docu-series Adventure, Zambezi. Episode 3: The Ancient Highway (1965)

David Attenborough retraces the steps of the famous Scottish explorer Dr David Livingstone in the final part of his African adventure.

Gwembe Valley Workshops

2024

Within the scope of the programme, I will be undertaking research and fieldwork across the Gwembe Valley, home to baTonga women who hold living histories of cisita. The framing and structure of the research has been radically reimagined as storytelling and sharing gatherings, in the form of three separate workshops which have been developed in order to challenge the position and value of baTonga women as experts in the fields of ‘botany’ and ‘jewellery making’.

Cisita research development

FEBRUARY 2024

The first activity of the Historians in-Residence program is a Research Field Trip requiring travel into three villages in the Gwembe Valley in order to:

Conduct preliminary research on the current living histories and community archives around cisita.

Establish the modalities of planning open knowledge sharing workshops, storytelling gatherings and archiving practices around cisita. These gatherings will be led by women in and from the Gwembe Valley, as well as the research team led by Banji Chona. This is structured in this way to nurture two eyed seeing. The research lead will collaborate with a community consultant in each of the three villages in order to identify and begin working with the aforementioned women.

The first gathering is a workshop on mabono, the castor plant. This all day gathering will be led by the herbalists/botanists. The castor plant has been identified and documented as a useful plant to baTonga in the process of cisita piercing. The second gathering will be centred on the various ornamental dressing or jewellery of cisita. An all day gathering will be led by jewellery makers who will centre the teachings around the materials, design principles and symbolism in the pieces of jewellery that were made to dress the cisita piercing. The main focus in this workshop will be to actively learn through observation and then document the process of making an array of different types of ornamental cisita pieces or jewellery. The final gathering of the body of work will be an all-day gathering led by Banji Chona and the research team who will be focused on the concept of metadata healing within the frameworks of museology. During this metadata healing gathering a series of images and renderings or objects, where obtainable, of different variations of cisita which have their provenance in the Gwembe Valley but are currently part of foreign museum collections will be shared with the group of women.

After the research segment of part I of cisita the original ornaments will remain in their place of provenance or with their principal maker. The output would exist as digitised, 3D reconstructions of the cisita ornaments made during the Gwembe Valley workshops. The digitised ornaments will be uploaded to The Shared Histories Digital Heritage Repository, an open-source learning initiative by the Women’s History Museum of Zambia to be made available for the public.

African Digital Heritage has a team or the networks that specialise in 3D digital reconstruction. Part of the Residency support would be the skill-sharing around the technology of 3D reconstruction to aid in the realisation of the above output as well as documentation of the various vernacular architecture in the area.

Cisita research development

APRIL 2024

Since the proposal of the research plan a few details have morphed, those of which I will share and give reason to the structural changes below.

The initial plan stated, “The first activity of the Historians in-Residence program is a Research Field Trip requiring travel into three villages in the Gwembe Valley in order to…” Two things have changed within this approach. The first has already been alluded to and is the change in the name of reference of the place in which the workshops will take place. As opposed to being called villages, which upon reflection lacks context and lustre within the frameworks of a radical practice, the places and the people will be called research partners. A way to mend some of the asymmetries present in non-critically employed research practice.

The second is the number of research partners to be included in this workshop or gathering based iteration. As opposed to aiming for breadth of research I have chosen to aim for attaining depth instead. This means employing laser-like focus on one particular area. The chosen community to formulate the gathering is kwaNyanga. A village in the Sinazongwe District in the Gwembe Valley. Located close to Maamba and Mweemba.

The co-researcher (previously research assistant, changed for similar reasons as stated above) Jackson was born in Nyanga and moved to Lusaka in search of a job. This is how Jackson and I met and why he has been chosen as the co-researcher. Jackson works in my family home in Lusaka, mainly looking after my grandfather. He is essentially family.

As it stands, Jackson has accepted the research position and is already in communication with people in his home of Nyanga as a means to identify the two women who will lead the botanical and jewellery making workshops in this area. To this end Jackson has received an advance payment as well as a stipend to cover his communications and research which is ensuing in mostly phone call form.

In a few weeks, Jackson will introduce me to the women in order to begin forming honest and open relationships with the women. The collaborators and drivers of this project. Another important note is the relationships I build with my research partners and co-researcher. These are grounded on a shared humanity and a shared value in being transmitters of knowledge the world is in dire need of.

The plan is to travel to kwaNyanga in June to meet the two women from this village in person and conduct the gatherings. In the meantime remote research is being continually conducted.

Research is currently being compiled on the history of kwaNyanga by Jackson

About Sinazongwe

Sinazongwe is a town in the Southern Province of Zambia, lying on the north shore of Lake Kariba. It was constructed in the 1950s as a local administrative centre, while its main industry now is kapenta fishing. It is also home to a lighthouse and an airstrip, while ferries sail to Chete Island. Sinazongwe also boasts The Houseboat Company.[1]

Sinazongwe is accessible nearly all year round. Access is by tar road from Batoka (which is between Pemba and Choma) and by 17 kilometres (11 mi) of gravel road just outside Sinazeze Town. The nearest airstrip is approximately 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) from Sinazongwe. The nearest large hospital is at Maamba which is about a 40-minute drive from Sinazongwe; however, there is a small hospital in Sinazongwe as well as a local clinic.

from wikipedia

A gallery of imagined outputs of the jewellery workshops kwaNyanga. Materials include copper, iron and reeds.

A gallery of imagined scenes of the fields of mbono-bono (ricinus communis) kwaNyanga and en route. Real life scenes will be added during and after the trip

“Poems about Piercings”

is one of the cisita outputs comprised of a collection of revisited thoughts and words explicity expressed towards me, often by strangers, about my septum piercing/cisita. It highlights experiences of alienation and invasion whilst alluding to the possibility of reimagining cisita as an expression of empowerment and cultural heritage preservation.

When traced cisita is derived from baTonga body adornment practices and expressions.

Contemporary narratives around piercings within Zambia are mostly constrained by post-colonial imagination, reflected in a range of thoughts around cisita or rather its ‘modern’ version, the metal horseshoe which I have been wearing for six years.

"Didn’t that hurt? Isn't your nose piercing the same as self mutilation? How do your parents feel?"

Lusaka, Zambia. 2019

“Iye, we mwana e finshi ifyo pa mfeshi? So tawu pepa ka? So niwe ulengesha amabasi a pilibuke” (spoken in Bemba)

Young one, what are all those things in your face? This means you don't pray. You're the reason these buses overturn.

Kapiri Mposhi, Zambia. 2019

a rendered image of a reimagined metal horseshoe septum ring/cisita informed by baTonga colour theory used in the design of beaded casings that encapsulated the original reed cisita adornment.

“Nga wachi ba umukashi wandi, ngalikufumisha ifintu fyobe fyonse mu moona. Elo lwacha akasuba epo wabuka ukekala uwa fulungana pantu ama nose ring naya fuma.” (Spoken in Bemba)

If you were my girlfriend, I’d watch you peacefully fall asleep at night and when you were asleep, I'd take all your piercings out and you'd wake up in the morning, confused as anything, patting yourself down trying to find your metal.

Kapiri Mposhi, Zambia. 2019

“Ino, donna. Nkanzi ako kantu mu mpemo? Uyoya buti?” (Spoken in Tonga)

Now, my lady. What is that thing in your nose? How do you breathe?

Lusaka, Zambia 2020

PART II

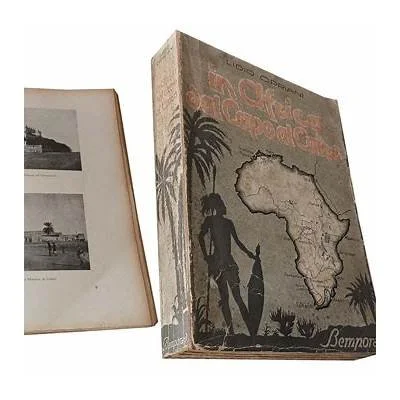

The second part of the research project is centred around challenging and reimagining the position that Anthropology, Botany, Phrenology and Museology as Western schools of thoughts occupy in the post-colonial imagination. They have, throughout time, created and cemented asymmetrical and in many cases damaging projections and depictions which still serve the violent nature of the post-colonial imagination. These frameworks of thinking will be explored and critiqued through the analysis of the work Italian anthropologist, Lidio Cipriani. Various threads of thought and expression that followed and informed his framework of theory and practice will also be analysed.

The output focus will be around the use of the visual corpus collected and archived by Cipriani and his various schools of thought, as the bases of critical installation pieces, like plaster facial casts, digital collages and aural sculptures, which aim to disrupt the occidental lens of documentation and the current catastrophic archive.

IN AFRICA DAL CAPO AL CAIRO. - Cipriani Lidio. - Bemporad, - 1932

In 8° (25,5x18 cm) XXVIII-633(2) pp., 286 foto e incisioni originali, 9 cartine e schizzi fuori testo (alcuni ripiegati). Prima e unica edizione pubblicata sotto gli auspici della R.Società Geografica italiana. Carta in perfette condizioni, grandi margini. Brossura editoriale a colori, esemplare freschissimo.

IN AFRICA FROM THE CAPE TO CAIRO. - Cipriani Lidio. - Bemporad, - 1932 In 8° (25.5x18 cm) XXVIII-633(2) pp., 286 original photos and engravings, 9 maps and out-of-text sketches (some folded). First and only edition published under the auspices of the Italian Geographical Society. Paper in perfect condition, large margins. Color editorial paperback, very fresh copy

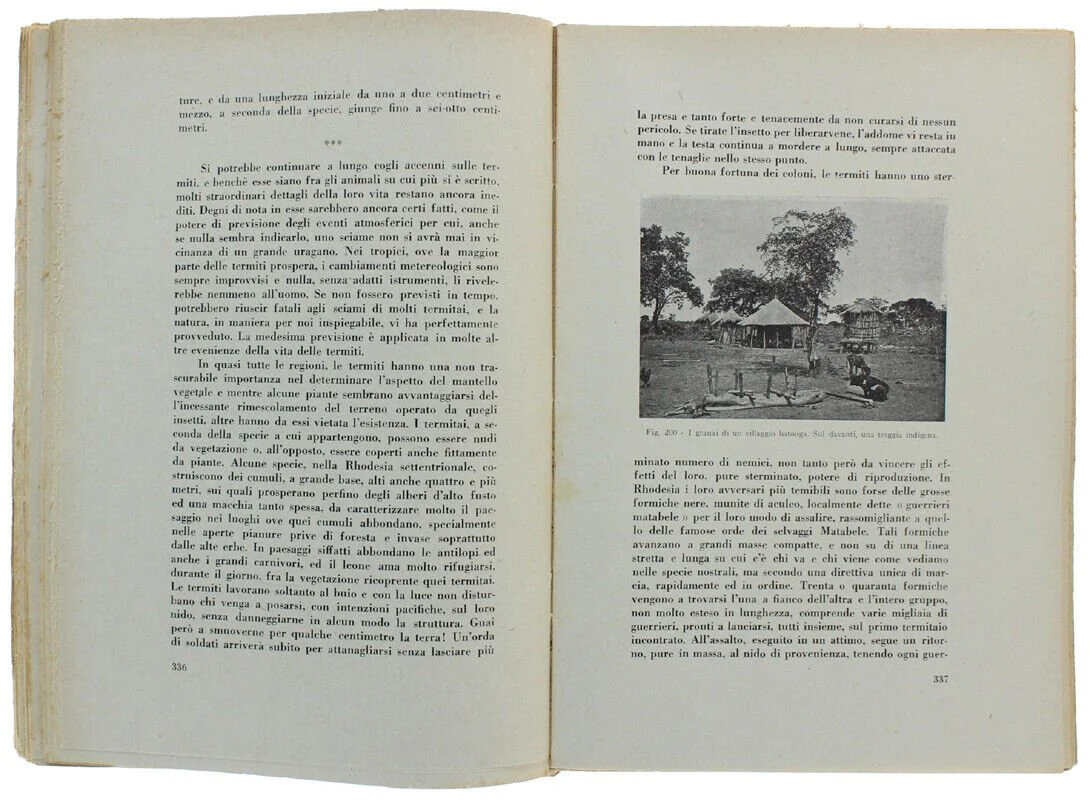

figure 200. I granai di un villagio batonga.

figure 200. I granary in a batonga village

Figure 2. Lidio Cipriani moulding a facial cast on a living individual, Zululand (Kwa-Zulu Natal), South Africa, 1927 (1/2) © Museum of Natural History of Florence, Anthropology and Ethnology Section, Photographic Archives, no. 4506

Calchi facciali di Lidio Cipriani. 1927-1930. Gesso policromo. Ciascuno 25x25x15cm. Proprietà del Museo di antropologia dell'Università di Padova. Esposti alla Mostra "Imago Animi. Volti dal passato". Palazzo Assessorile di Cles.

Facial casts of Lidio Cipriani. 1927-1930. Polychrome plaster. Each 25x25x15cm. Property of the Anthropology Museum of the University of Padua. Exhibited at the "Imago Animi. Faces from the past" exhibition. Cles Councilor's Palace.

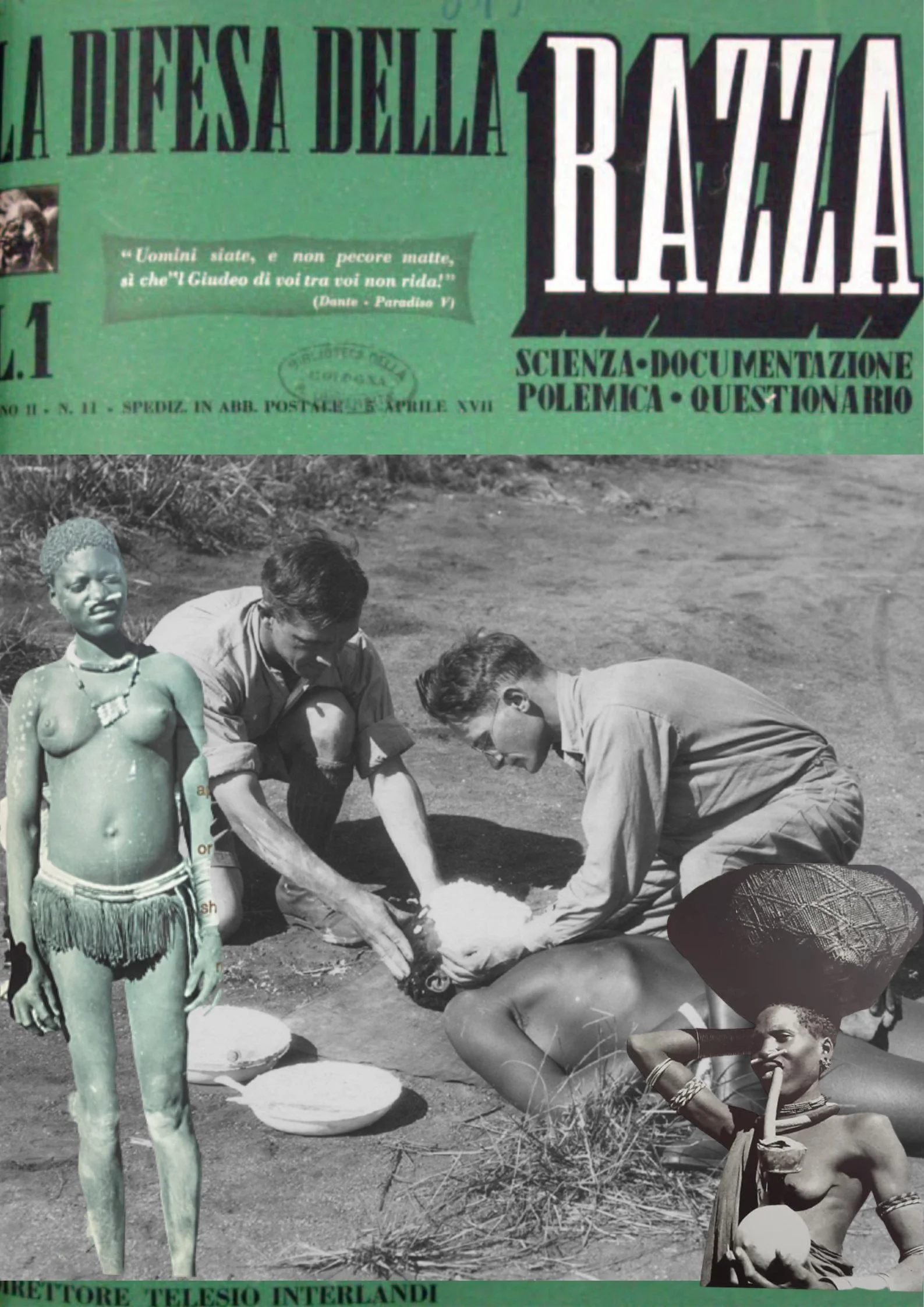

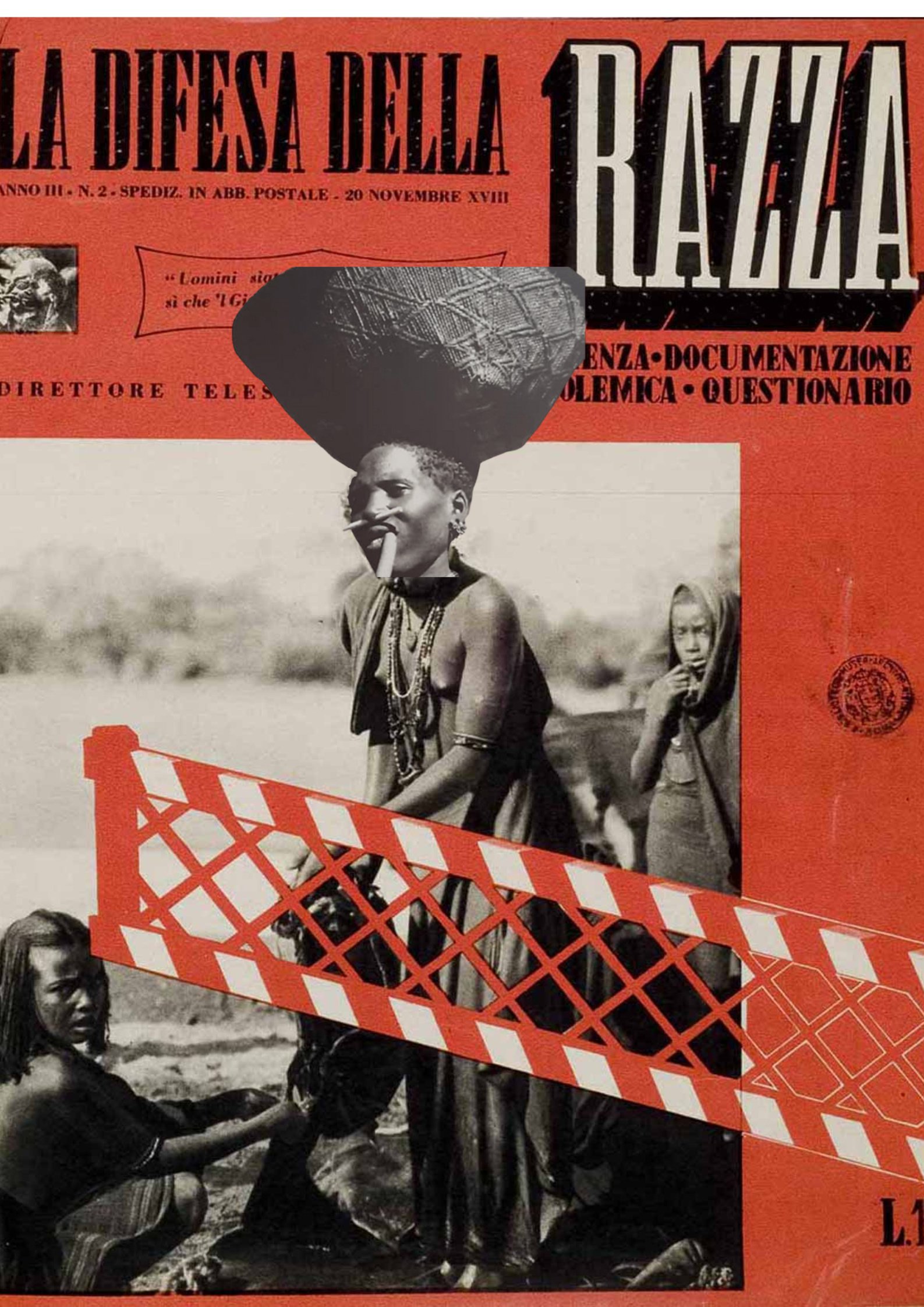

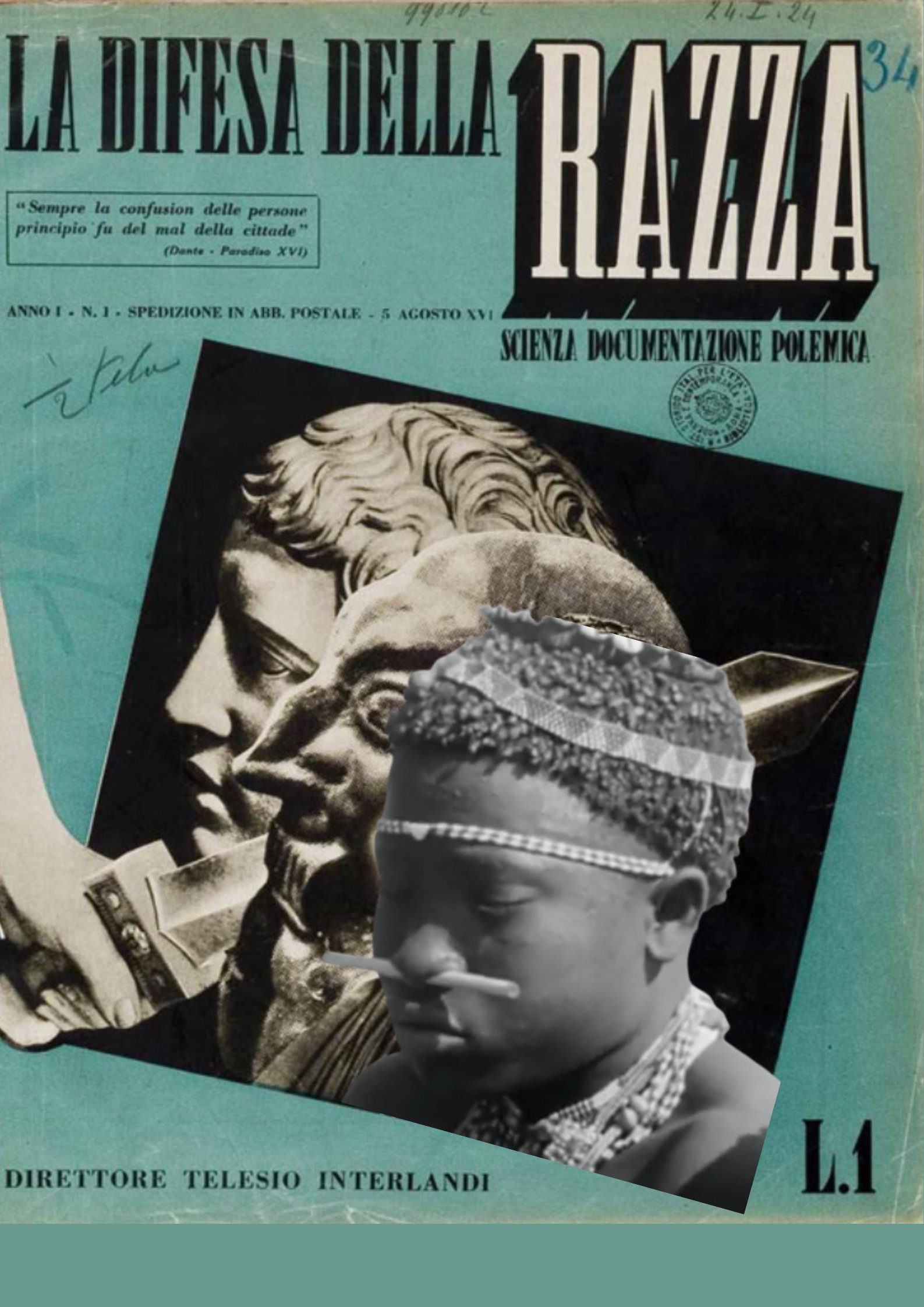

Collage Pieces

untitled (2022)

The untitled collage pieces in the Cisita series use the covers and images put forward by La Difesa Della Razza as a way to distort and thus question the role of visual representations;anthropological photographs; facial casts in the construction of a mass racial ideology

La Difesa della Razza (Italian: In Defence of Race) was a Fascist biweekly magazine which was published in Rome between 1938 and 1943 during the Fascist rule in Italy. Its subtitle was Scienza, Documentazione, Polemica (Italian: Science, Documentation, and Debate).[1] It played a significant role in the implementation of the racial ideology following the invasion of Ethiopia and the introduction of the racial laws in 1938.[2][3]

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The first issue of the magazine featured a manifesto, Manifesto della Razza, by the scholars which was the guiding principle of the racist ideology of Fascist Italy.[10] Following the publication of this manifesto the approach of the state towards the Italian Jews and its colonial policies changed.[10] The magazine described its goals in the first issue as follows:[10]

We will popularize, with the help of scholars of various disciplines related to the problem, the fundamental concepts upon which the doctrine of Italian racism is based; and we will prove that science is on our side.

La Difesa della Razza often featured graphics, photographs, cartoons and photomontages accompanied by offensive and vulgar captions.[1] Its headlines were mostly sensationalist.[1] The magazine was a supporter of the pseudoscience,[11] cultural racism and Italian primitivism rejecting the premises of European modernism.[3] The most frequent topic covered in the magazine was about antisemitism.[9] In May 1942 in the article by Giorgio Almirante blood was regarded as the sole evidence of Italianness which differentiated Italians from Jews and Black mixed race people.[11] Both groups were depicted in a negative manner in the magazine through photographs.[9] In 1942 and 1943 the magazine claimed that the British had a cruel attitude towards people living in its colonies.[12]

Some of its contributors were Lino Businco, Luigi Castaldi, Elio Gasteiner, Guido Landra and Marcello Ricci who were scientific figures and published articles about biological racism.[7] Guido Landra's articles were mostly concerned with hereditary diseases.[7] Ferdinando Loffreda regularly wrote articles for the magazine in which he offered his antifeminist views.[13]

Shortly after its launch La Difesa della Razza sold 150,000 copies per issue.[9] However, from November 1940 its circulation significantly decreased because of the start of World War II.[9]

References

^ Jump up to: a b c Federica Durante; Chiara Volpato; Susan T. Fiske (2009). "Using the stereotype content model to examine group depictions in Fascism: An archival approach". European Journal of Social Psychology. 40 (3): 467. doi:10.1002/ejsp.637. PMC 3882081. PMID 24403646.

^ Jump up to: a b c d Sandro Servi (2005). "Building a Racial State: Images of the Jew in the Illustrated Fascist Magazine, La Difesa della Razza, 1938–1943". In Joshua D. Zimmerman (ed.). Jews in Italy under Fascist and Nazi Rule, 1922–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 114–157. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511471063.010. ISBN 9780511471063.

^ Jump up to: a b c Mariana Aguirre (October 2015). "La Difesa Della Razza (1938–1943): Primitivism and Classicism in Fascist Italy". Politics, Religion & Ideology. 16 (4): 370–390. doi:10.1080/21567689.2015.1132412. S2CID 146984963.

^ Jump up to: a b c "The Defense of the Race magazine". Museo Ebraico. 18 July 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

^ Jump up to: a b c Aaron Gillette (Winter 2002). "Guido Landra and the Office of Racial Studies in Fascist Italy". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 16 (3): 361. doi:10.1093/hgs/16.3.357.

^ Aaron Gillette (2001). "The origins of the 'Manifesto of racial scientists'". Journal of Modern Italian Studies. 6 (3): 308. doi:10.1080/13545710110084253. S2CID 146603137.

^ Jump up to: a b c Francesco Cassata (2011). Building the New Man: Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy. Budapest: Central European University Press. pp. 223–284. ISBN 9789639776838.

^ David I. Kertzer; Gunnar Mokosch (2020). "In the Name of the Cross: Christianity and Anti-Semitic Propaganda in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 62 (3): 461. doi:10.1017/s0010417520000146. S2CID 225528189.

^ Jump up to: a b c d e Chiara Volpato; et al. (December 2010). "Picturing the Other: Targets of Delegitimization across Time". International Journal of Conflict and Violence. 4 (2): 272–276. doi:10.4119/ijcv-2831.

^ Jump up to: a b c Barbara Sòrgoni (2003). "'Defending the race': the Italian reinvention of the Hottentot Venus during Fascism". Journal of Modern Italian Studies. 8 (3): 412. doi:10.1080/09585170320000113761. S2CID 143675594.

^ Jump up to: a b Angelica Pesarini (2022). ""Africa's Delivery Room": The Racialization of Italian Political Discourse on the 80th Anniversary of the Racial Laws". In Marcella Simoni; Davide Lombardo (eds.). Languages of Discrimination and Racism in Twentieth-Century Italy. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 207. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-98657-5_9. ISBN 978-3-030-98657-5.

^ Jacopo Pili (2021). "The Representation of British Foreign Policy". Anglophobia in Fascist Italy. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 37. doi:10.7765/9781526159663. ISBN 9781526159663. JSTOR j.ctv2cmrbq3.4. S2CID 247310834.

^ Alexander De Grand (1976). "Women under Italian Fascism". The Historical Journal. 19 (4): 966. doi:10.1017/s0018246x76000011. S2CID 159893717.