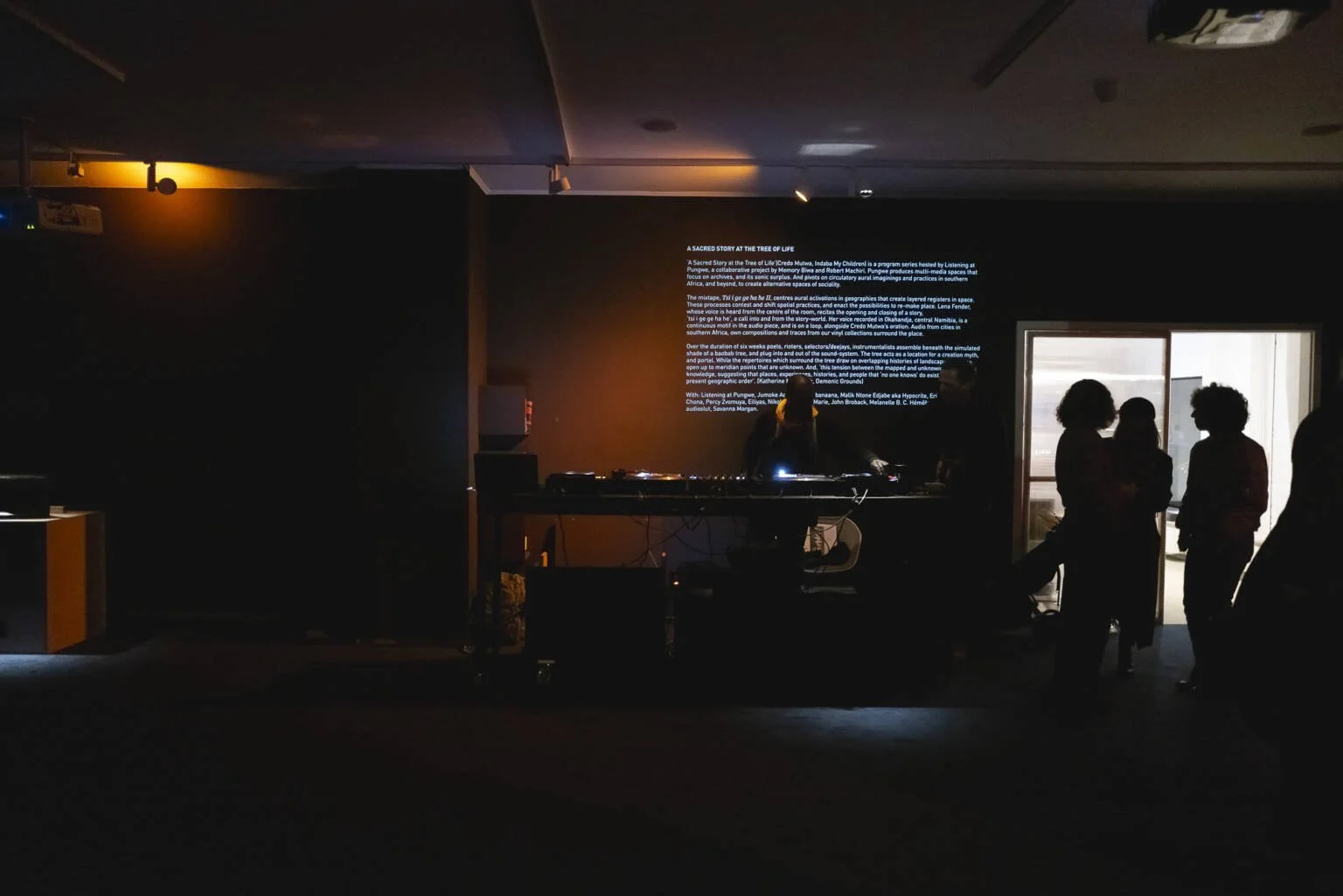

A SACRED STORY AT THE TREE OF LIFE takes the form of an ephemeral installation centered on the inscription and significance of landscapes and spaces through memory and ceremony. The shade of the baobab, the sacred tree, becomes the gathering place where we commune with poets, rioters, storytellers, vocalists, players of instruments, and DJs. Pungwe is an occasion where sound system culture is approached as a mo(nu)ment of auditory, corporeal and sociocultural frequencies. The platform traces spatiality through a complex web of movements that are often embodied and transferred through sound.

The title echoes Sanusi Vusamazulu Credo Mutwa’s Chapter, ‘The Sacred Story of the Tree of Life’, in "Indaba My Children: African Tribal History, Legends, Customs and Religious Beliefs", Canongate Books Ltd, Edinburgh, 1998, first published in 1964.

Participating artists: Listening at Pungwe, Jumoke Adeyanju‚ blk banaana , Banji Chona, Malik Ntone Edjabe, Percy Zvomuya, Elsa M’Bala, Melanelle B. C. Hémêfa, Day Eve & Savanna Morgan et al.

Curatorial Ensemble: Memory Biwa, Robert Machiri, Jumoke Adeyanju, Nikola Hartl

Memory Biwa is a historian, and artist. Her work addresses memorial and reparative processes in Namibia, which encompasses a wider discourse on restitution and reparations. Biwa’s focus on oral narratives and performance informs notions of subjectivity and the re-centering of alternative epistemologies and imaginaries.

Robert Machiri is a sound artist and hoarder of sound-related objects. Machiri’s work exists at the juncture of two streams of practice; curatorial concepts founded through the notion of conviviality and art as pedagogy. Biwa and Robert Machiri form the duo, Listening at Pungwe.

Within this installation, Restorying Space was a framework birthed in dialogue by Memory Biwa and myself, as a guiding principle or base to create an aural sculpture’. The aural sculpture, ‘Tulila Meenda’ is my interpretation of both celebration and critique of an ‘ethnographic’ recording of the same title on a 1957 compilation of recordings by Hugh Tracy entitled ‘Topical and ceremonial songs including rain songs from the Valley Tonga people of Zambia’. It is an incantation directed to Basangu, the baTonga’s god-like ancestors and custodians of the natural world, both in flesh and spirit. This piece is a duet between the principal rainmaker Simalende and the custodians of the Malende, a chorus of women or ancestral mothers. This style of song or music is called Kukambilana, it was expressed during times of celebration. The choirs formed a circle in which they would take turns stepping into, clapping, ululating and dancing.

Restorying Space can be defined as the restoring of stories that are rooted in the significance of objects, landscapes and spaces as places of memory, ritual and ceremony. Within the context of baTonga, physical or natural landscapes are portals or tangible reminders of ancestral practice and knowledge which have long existed in the Zambezian context. Stories of past, present and future are layered and inscribed in nature; in mounds of red clay, in the outer bark of trees, in hills and in rivers. The framework was used to guide my reworking of the loss of the sacred and integral role of nature in our active practices of ritual and memory. Deeply reconnecting with nature is a reminder to remember ourselves as baTonga, our ancestral pasts and the deep symbiosis they held with the natural world.

Malende (rain shrines), are conceived in baTonga spiritual belief and ecological ritual as spaces, objects and practices deeply rooted in nature. They are the conduits for healing and where healing continues to multiply. Malende are symbols of resilience and resistance. Places to worship and celebrate, to tap into community, memory, celebration and technique. Potential bridges of reconnection from ancestral pasts to presentisms. In baTonga spiritual belief, malende are the dwelling places of Basangu, benevolent guiding spirits. Ancestors who were celebrated during ritual and celebration. Malende were often mounted or ascribed to natural sites like trees, or hills, many ceremonies of gathering took place, song was sung, libation was poured unto terra.

Through Tulila Meenda, I allude to the many layers of voices, both literal and spiritual or metaphorical, present in the aural ritual surrounding Malende. The aural sculpture uses sonic role reversal as a means to challenge the patriarchal role of Simalende (guardian of the rain shrine) in spiritual practices. I use my voice through poetic interpretation to juxtapose the leading voice of the Simalende in the original audio. This on the whole leads to a portal of inquiry into the missing voices of women within ancestral narratives.

This inquiry is based on the notion of trusting memory over history, as a rebellion against single story narratives that have been written down and quantified as History. ‘Memory, like fire, is radiant and immutable while history serves only those who seek to control it, those who douse the flame of memory in order to put out the dangerous fire of truth. Beware these men for they are dangerous themselves and unwise. Their false history is written in the blood of those who might remember and of those who seek the truth.’(Floyd Crow Westerman)

Memory tells us women were often the mediums between the ancestral spirits and the living realm; between nature and people. In my home village of Nampeyo also known as KwaCona, during Lwiindi lwa Buloongo (festival to honour the soil) women would often lead the celebrations held across many chiefdoms. In preparation, they would source fruit and crop from nature's bountiful banquet, brew gankata, a beer from ancestral grain and gather in the spirit of community to give thanks to the ancestral spirits who dwell within the soil and nature as a whole. One of the core concepts of BaTonga society and life is community fellowship; the spirit of togetherness.

The day before the ritual, Simalende, the earthly spirit medium, would visit the shrines and pour libation, invoking the ancestral spirits to intercede in the prayers of thanksgiving and good rain. On the day of lwiindi lwa buloongo, at the rain shrine, women would gather around the sacred hut barefooted and dressed in black outfits singing incantations of praise and supplication. The black in their regalia was to signify communion with the nimbus clouds, which they beckoned for rain. We believe we are all of the same matter. Their bare feet represented a rooting and deeper connection to that which they came from.

Outside of their roles at the rain shrine rituals which were sporadically marked throughout the year, Simalende played an important role maintaining the health and symbiosis of and between people, plants and animals. Nangoma is one of the Simalende and ancestral mothers of direct kin, who is revered in memory as a protector of the natural world and of human life. Nangoma, as Simalende, possessed supernatural abilities which allowed her to commune with the natural world. It is said that she kept a snake in the doorway of her home (kaanda) as an expression of her abilities as a medium between worlds. baTonga spiritual belief and practice relied on decoding messages from the ancestors which were imbued in nature. Snakes, tortoises and crocodiles were common symbols of messages from Basungu about ecological order or natural occurrences, like rain. If a snake was seen a number of times by Simalende and village elders it signified a ritual would need to occur in order for the community to comprehend and receive the wisdom of the ancestral spirits. A woman would be instructed to take a handful of sorghum or millet flour to the malende and dust it over the resting place of the snake. Once that was done Simalende would continue in communion with the spirits to seek their counsel in community life.

The baTonga spiritual belief system says illnesses and outbreaks that affected the wider community were caused by the upset of the ancestral spirits, as they were the supernatural protectors of the living world. In 1893, a smallpox outbreak swept across Nampeyo and a large portion of the Southern and Western Provinces of Zambia. As Nangoma was the Simalende of the area, she was consulted by members of the community on how to heal the outbreak. She visited the malende, placed sacred objects like clay pots (tunongo) in front of the Basangu who presented her with herbal remedies from nature's banquet to combat the outbreak. It is said that only two people in Nampeyo died from the outbreak, in comparison to the hundreds who died in neighbouring communities.

Nangoma is one of the Simalende who still have a surviving shrine in her commemoration in our home village of Nampeyo, ‘kaanda kokwa Nangoma’. This shrine is still maintained by the people of the community who still visit it to be healed and guided by her eternal counsel. Although this is the case in KwaCona, it is written that Malende often do not survive their custodians or communities (Colson, 1948).

Leading Ladies Visual Podcast

Women’s History Museum of Zambia

Nangoma, the Rainmaker (S04 E03)

Nangoma, a rainmaker that understood that an environment with healthy regenertaing plants, water and animal life was necessary for a community to have stable families, peaceful lives, prosperity, adequate food and security.

Within the contemporary context and thus within the post-colonial imagination Simalende and Malende as a practice have diminished or disappeared as belief systems have changed or communities have migrated to urban areas. The decline in ecological ritual practice has affected the symbiotic relationship between baTonga and the natural world and thus the care of the natural world. Another reason for the decline in the practice can be linked to the arrival of the colonial government and their imposition of Native Tax Laws. The Simalende who were spiritual leaders anointed and chosen by the ancestors were converted, by law, into appendages of the colonial government becoming what we now know as chiefs and headmen. Simalende have morphed throughout time into Sibukku which is the common term for a headman in baTonga settlements. Sibukku directly translates as the one holding the (tax)book. Within the context of these socio-political and spiritual shifts and the establishing of colonial power structures, rooted in patriarchal philosophies, women and their roles within society were silenced and subjugated. This body of work is a portal into reimagining the role of Simalende and women in the revival of ecological rituals, like Malende.

Transcript of Poetic Interpretation

My people, we should test the temperatures.

Listen to the rumbles of our ancestors,

To the stories my child sings.

The songs she sings of rain.

Look above, the skies have dried up,

beckoning our prayers and libation.

We sing incantations of water;

Of the long rains that fill the Zambezi

And evoke mighty waves

We cry for the downpour that seals our harvest.

Clap at the motion of our cattle grazing fields of sprouts tender.

We don our backs in cloth blackened

Commune with the nimbus clouds tarry and heavy;

Our feet bare rooting in earth as rattles coat a nectar of sound.